Anatomy and Dimensions

The gray wolf is the largest extant member of the Canidae, excepting certain large breeds of domestic dog. Gray wolf weight and size can vary greatly worldwide, tending to increase proportionally with latitude as predicted by Bergmann's Rule, with the large wolves of Alaska and Canada sometimes weighing 3–6 times more than their Middle Eastern and South Asian cousins. On average, adult wolves measure 105–160 cm (41–63 in) in length and 80–85 cm (31–33 in) in shoulder height. The tail measures 29–50 cm (11–20 in) in length. The ears are 90–110 mm (3.5–4.3 in) in height, and the hind feet are 220–250 mm (8.7–9.8 in). The mean body mass of the extant gray wolf is 40 kg (88 lb), with the smallest specimen recorded at 12 kg (26 lb) and the largest at 80 kg (180 lb). Gray wolf weight varies geographically; on average, European wolves may weigh 38.5 kg (85 lb), North American wolves 36 kg (79 lb) and Indian and Arabian wolves 25 kg (55 lb). Females in any given wolf population typically weigh 5–10 lb (2.3–4.5 kg) less than males. Wolves weighing over 54 kg (119 lb) are uncommon, though exceptionally large individuals have been recorded in Alaska, Canada, and the forests of western Russia. The heaviest recorded gray wolf in North America was killed on 70 Mile River in east-central Alaska on July 12, 1939 and weighed 79.4 kg (175 lb).

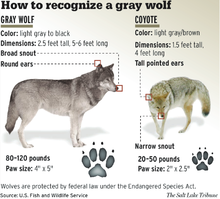

Compared to its closest wild cousins (the coyote and golden jackal), the gray wolf is larger and heavier, with a broader snout, shorter ears, a shorter torso and longer tail. It is a slender, powerfully built animal with a large, deeply descending ribcage, a sloping back and a heavily muscled neck. The wolf's legs are moderately longer than those of other canids, which enables the animal to move swiftly, and allows it to overcome the deep snow that covers most of its geographical range. The ears are relatively small and triangular. Females tend to have narrower muzzles and foreheads, thinner necks, slightly shorter legs and less massive shoulders than males.

The gray wolf usually carries its head at the same level as the back, raising it only when alert. It usually travels at a loping pace, placing its paws one directly in front of the other. This gait can be maintained for hours at a rate of 8–9 km/h (5.0–5.6 mph), and allows the wolf to cover great distances. On bare paths, a wolf can quickly achieve speeds of 50–60 km/h (31–37 mph). The gray wolf has a running gait of 55–70 km/h (34–43 mph), can leap 5 m (16 ft) horizontally in a single bound, and can maintain rapid pursuit for at least 20 minutes.

Skull and dentition

The gray wolf's head is large and heavy, with a wide forehead, strong jaws and a long, blunt muzzle. The skull averages 230–280 mm (9.1–11.0 in) in length, and 130–150 mm (5.1–5.9 in) wide. The teeth are heavy and large, being better suited to crushing bone than those of other extant canids, though not as specialised as those found in hyenas. Its molars have a flat chewing surface, but not to the same extent as the coyote, whose diet contains more vegetable matter. The gray wolf's jaws can exert a crushing pressure of perhaps 10,340 kPa (1,500 psi) compared to 5,200 kPa (750 psi) for a German shepherd. This force is sufficient to break open most bones. A study of the estimated bite force at the canine teeth of a large sample of living and fossil mammalian predators when adjusted for the body mass found that for placental mammals, the bite force at the canines (in Newtons/kilogram of body weight) was greatest in the extinct dire wolf (163), then followed among the extant canids by the four hypercarnivores that often prey on animals larger than themselves: the African hunting dog (142), the gray wolf (136), the dhole (112), and the dingo (108).